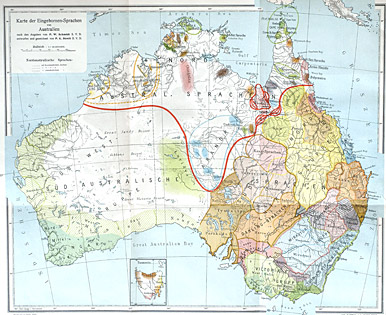

Map from Schmidt, Wilhelm 1919. Die Gliederung der australischen Sprachen. Geographische, bibliographische, linguistische Grundzüge der Erforschung der australischen Sprachen. Wien: Mechitharisten-Buchdruckerei. Copyright by Mechitharisten-Kloster. This map is one of the earliest maps which show geographical distributions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages.

AustLang provides a controlled vocabulary of persistent identifiers, a thesaurus of languages and peoples and information about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages which has been assembled from referenced sources.

The alpha-numeric codes function as persistent identifiers, followed by a 'string of changeable text'. This allows changes to the name or spelling of a language variety, according to community preference. In cases where there is more than one preference, two or three versions of the name are included, e.g. E6: Dhanggati / Dunghutti^.

This vocabulary of persistent identifiers supports archives, libraries, galleries and other agencies to identify materials or projects in or about Indigenous Australian languages and peoples, without the confusion of a multitude of language names and spellings. The codes maintain an identity if a change is made to the spelling or the name.

AustLang can be searched with language names (including a range of spellings); the codes, for example E6; placenames and via the map. AustLang has links to MURA the AIATSIS catalogue and other online resources.

EMAIL: austlang@aiatsis.gov.au

AustLang contains the following information about each Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander language:

- Alternative/variant names and spellings

- A comment about the language variety from referenced sources

- Geographical location from referenced sources

- Authority headings for languages and peoples

- Links to MURA the AIATSIS catalogue and OZBIB a curated bibliography (up to 2013).

- Links to Trove, Worldcat, Tindale, OLAC, SIL

- Programs and people involved in language maintenance and revival

- History of the number of speakers

- Documentation scores for known word lists; text collections; grammars; audio-visual resources (up to 2007)

- Classifications from various linguistic surveys 1966−2005.

Content disclaimer AustLang is presented largely from a research perspective and may not necessarily be consistent with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives. The system assembles information from a number of sources without assessing the validity and truthfulness of that information. AIATSIS makes no representations, warranties or assurances (either expressed or implied) as to the accuracy, currency or completeness of the information presented. AIATSIS will not be held liable for any damage that may arise from use of or reliance upon any information provided by this system, or from your inability to use the system. AIATSIS reserves the right to add, delete and/or modify any information on the site at any time without prior notification.

Location of languages Users of this system are advised that locations of languages shown on the map are approximate and not to be used for land or native title claims. AustLang offers representations of language locations, which are neither authoritative nor definitive.

History of AustLang

- 1990s 'Australia's Languages' HyperCard stacks developed by Nick Thieberger.

- 2001 Nick Thieberger migrated the information from HyperCard stacks to a Filemaker Pro file to form the basis of the Indigenous Languages Database (ILDB).

- 2003: Specifications drafted for a web-enabled Indigenous Languages Database based on ILDB data.

- 2004: The University of Melbourne contracted to provide programming work.

- 2005: Initial version of AustLang released.

- 2007: The Australian National University contracted to provide programming work for new version.

- 2008: AustLang released to the public.

- 2016: AIATSIS develops plans to migrate AustLang to a new platform incorporating persistent identifiers and the former Languages and Peoples Thesaurus authority headings.

- 2018: AustLang was refined and redeveloped for deployment on the new Collections platform, which supports interoperability with other online systems.

- 2018: Library of Congress adds AustLang codes to MARC Language Source Codes.

- 2019 AustLang datasets (codes, reference names, authority headings and map locations released under CC BY 4.0 license.

Language codes and reference names

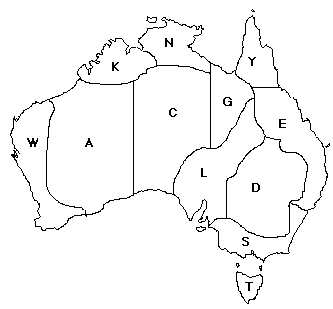

Indigenous Australian languages are known by a range of names and spellings, a result of haphazard incorporation into non-Indigenous knowledge systems. In order to maintain the identity of a language, AIATSIS assigns an alpha-numeric code to each language variety, with a community preferred name and spelling, to form a reference name. The letter in the code represents a specific region shown on the map below (note that P is used for creoles and Aboriginal English and T for Tasmanian language varieties). This system was devised by Arthur Capell for his 'Linguistic Survey of Australia' prepared for the former Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies in 1963, https://aiatsis.gov.au/blog/arthur-capell-and-language-codes:

Some reference names are used as both a language and a dialect name; some as either a language or a dialect name. When a name is used as both a language and a dialect name, this is indicated by ^, for example, the name Kala Lagaw Ya^ is used as both a language name and a dialect name – the Kala Lagaw Ya^ (Y1) language has the following dialects: Y2: Kalaw Kawaw Ya, Y4: Kulkalgaw Ya, Y5: Kawalgaw Ya, and Y1: Kala Lagaw Ya^ itself.

When a reference name is used only as a language name, with dialects listed separately, the language name is given in capitals. For example, N230: YOLNGU MATHA is used as a language name and the Yolngu Matha language has several dialects, but unlike the case of Y1: Kala Lagaw Ya^, none of these dialects are called Yolngu Matha.

In reality, there are not many reference names marked with ^ or capital letters because these conventions are employed only when relationships between languages and dialects are clear or a name is clearly used as a language name for a group of dialects. Further, these conventions are not employed when distributions of dialects are not clear. For example, Dench (1991:126) reports that speakers recognise two named dialects of A53: Banyjima: A76: Pantikura and A77: Milyaranypa, but it is not clear whether they cover the entire Panyjima speaking country or just parts of it. Therefore, A53: Banyjima is not given in capitals.

Languages, dialects, language varieties and peoples

In AustLang the distinction between languages and dialects are not always made, and the term 'language variety' is often used to refer to both language and dialect, or in some cases patrilects (see N104: Ritharrngu). In general, languages consist of dialects which are varieties (or different versions) of the language. Different dialects are mutually comprehensible and are described in terms of a dialect chain. When two neighbouring dialects (adjacent links in a chain) are compared, the differences are slight. A comparison between dialects from each end of the chain reveals significant differences, which makes mutual comprehension between some speakers more difficult. On the other hand, different languages are not mutually comprehensible and must be acquired or learnt.

Relationships between language varieties are described in a Comment. Note that a record in AustLang can be on either a language or a dialect. That is, languages are not the sole entries in AustLang. Dialects are not listed under a language. In effect this means that dialects are afforded equal 'status' as languages.

Some records represent group, clan or people names, for example N141: Gumatj. This record also contains an authority heading for language because there are materials in the AIATSIS Languages Collection described as 'Gumatj language'. The actual status of Gumatj as a Yolngu Matha clan is in the Comment. The inclusion of people names as AustLang records is a result of history: many people names have been mistaken for language names. In this iteration of AustLang many people or group names which are identified with spoken language are included. See N230: YOLNGU MATHA and the hierarchy of language varieties and their affiliated clan names for examples of this approach.

Many AustLang records refer to a people and not to a language variety, in the first place they were mistaken for a language variety name. Many people names have recently been added to AustLang, and YOLNGU MATHA N230 is a good example of this (see above). Some languages are affiliated with different peoples, see S47: Walgalu, affiliated with Walgalu, Ngambri and Ngurmal peoples which share the same code: S47. Some language varieties have people names different from the language name, but share a code see Y67: Flinders Island language and Aba Yalgayi people. Some language varieties and people records are separated, due to historical circumstances in their documentation see Y63.1: Barrow Point language affliliated with Y62: Ama Ambilmungu people. Finally some language varieties are affiliated with people with a different code, see Y136: Mbarrumbathama, Y55: Morrobolam, Y236: Yintyingka, Y195: Rimanggudinhma and Y50: Umpithamu, all affiliated with Lamalama people in modern times.

Library of Congress MARC language source codes

In October 2018 the Library of Congress accepted a proposal developed by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies and the National Library of Australia to add AustLang to the MARC Language Source Codes list. Libraries across Australia and around the world are now able to use an appropriate, authorised standard to identify Australian Indigenous language materials in their collections, replacing the single MARC language code ‘aus’ with alpha-numeric codes for hundreds of different language varieties: MARC language Source Codes list. AustLang provides identification of a more comprehensive range of Australian Indigenous languages than any other code currently recognised.

AustLang as a 'names' dataset

The starting point of AustLang was the Indigenous Languages Database (ILDB). This data was based on the Language Thesaurus formerly maintained and used by the AIATSIS Collections Services for cataloguing purposes from the 1960's. Since then research on Indigenous languages has revealed previously unknown languages; some language names have turned out to be place names; others have been confused with group (people) names; some names (called exonyms) are those given by neighbours, but not used by the speakers.

AustLang attempts to incorporate and present recent findings and list all names that have been reported to be a language or dialect name in the past. This includes language and dialect names which were not previously reported and names that were previously reported to be language name, but which turned out not to be so. In order to distinguish different types of names, for example names that are not a language, AustLang has a status field to distinguish different degrees of certainty about names. The distinction between ‘Unconfirmed’ and ‘Potential no data’ is not clear, since both categories include names with little information.

Datasets

The following datasets from AUSTLANG are available for download under CC BY 4.0 license from https://collection.aiatsis.gov.au/datasets and from https://data.gov.au/search?q=austlang.

- Codes and reference names

- Authority headings for languages and peoples

- Synonyms

- Approximate latitude and longitude of language varieties.

Data sources and references (bibliography)

The AustLang bibliography assembles information from a number of sources, including the following selection of materials.

- Australian Bureau of Statistic. 2005. Australian Standard Classification of Languages (2nd edition. 1267.0. Canberra: ABS. ABS data used with permission from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 1996. Census of Population and Housing, Languages Spoken at home (Australian Indigenous languages). Canberra: ABS. ABS data used with permission from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2001. Census of Population and Housing, Languages Spoken at home (Australian Indigenous languages). Canberra: ABS. ABS data used with permission from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2006. Census of Population and Housing, Languages Spoken at home (Australian Indigenous languages). Canberra: ABS. ABS data used with permission from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2011. Census of Population and Housing, Languages Spoken at home (Australian Indigenous languages). Canberra: ABS. ABS data used with permission from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2016. Census of Population and Housing, Languages Spoken at home (Australian Indigenous languages). Canberra: ABS. ABS data used with permission from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. 2005. National Indigenous Languages Survey report 2005. Canberra: Department of Communication, Information Technology, and the Arts.

- Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. 2014. National Indigenous Languages Survey report 2005. Canberra: Department of Communication, Information Technology, and the Arts.

- Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies & Australian National University. 2019. National Indigenous Languages Report 2019. Canberra: Department of Communication, Information Technology, and the Arts

- Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Language and Peoples Thesaurus. URL: http://thesaurus.aiatsis.gov.au/language/language.asp

- Horton, David. 1996. Aboriginal Australia. Canberra: AIATSIS: A map (1:4,700,000) of language/tribal/nation groups and their list. Online version of the map is available on https://aiatsis.gov.au/explore/articles/aiatsis-map-indigenous-australia

- Approved Subject Headings by Australian Bibliographic Network on Australian Aboriginal languages. URL: https://www.nla.gov.au/librariesaustralia/our-services/cataloguing-service/australian-extension-lcsh

- Baker, Brett. New Top End Handbook (FileMaker database) (ASEDA 0626).

- Clark, Ian. 1999. Aboriginal languages and clans: an historical atlas of Western and Central Victoria, 1800-1900. Melbourne: Monash Publications.

- Dixon, R. M. W. 2002. Australian languages: their nature and development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.). 2005. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. URL: http://www.ethnologue.com/

- Glottolog

- Harvey, Mark. 2008. Non-Pama-Nyungan Languages: land-language associations at colonisation. (AILEC 0802).

- McGregor, William. 1988. Handbook of Kimberley languages. Series title: Pacific Linguistics Series C-105. Canberra: RSPAS, ANU.

- Nash, David and Menning, Kathleen. 1981. Sourcebook for Central Australian Languages. Alice Springs: Institute of Aboriginal Development.

- Oates, W. J. and Oates, L. F. 1970. A revised linguistic survey of Australia. Australian Aboriginal Studies 33, Linguistic series 12. Canberra: AIAS

- Oates, Lynettte F. 1975. The 1973 supplement to a revised linguistic survey of Australia. Armidale: Christian Book Centre

- O'Grady, G N, Voegelin, C F, and Voegelin. F M. 1966. Languages of the world: Indo-Pacific fascicle six. Anthropological Linguistics 8(2).

- Schmidt, Annette. 1990. The Loss of Australia's Aboriginal language heritage. Canberra: AIATSIS: Overviews Aboriginal language situation; examines attitudes to language; analyses language maintenance and revival programs, bilingual education, effectiveness of funding and National Aboriginal Languages Program; availability of linguistic training, characteristics of language loss and the place of creoles in language programs.

- Thieberger, Nick. ILDB (Indigenous Language Database, filemaker database).

- Thieberger, Nick. 1993. Handbook of Western Australian Aboriginal languages south of the Kimberley region. Series title: Pacific Linguistics Series C-124. Canberra: RSPAS, ANU. URL: https://web.archive.org/web/20011217143806/http://coombs.anu.edu.au/WWWVLPages/AborigPages/LANG/WA/contents.htm

- Tindale, Norman. 1974. Aboriginal tribes of Australia: their terrain, environmental controls, distribution, limits, and proper names. First published by Berkeley: University of California Press and then by Canberra: Australian National University Press. Online version is available at http://archives.samuseum.sa.gov.au/tindaletribes/index.html. This site, the 'Catalogue of Australian Aboriginal Tribes', also provides information about Tindale's collection in the South Australian Museum Archives. The collection comprises expedition journals and supplementary papers, sound and film recordings, drawings, maps, photographs, genealogies, vocabularies and correspondence.

- Tindale, Norman. 1974. Tribal Boundaries in Aboriginal Australia. Canberra: Division of National Mapping, Department of National Development. Online version: http://archives.samuseum.sa.gov.au/tribalmap This map is a reproduction of N.B. Tindale's 1974 map of Indigenous group boundaries existing at the time of first European settlement in Australia. It is not intended to represent contemporary relationships to land.

(Tindale's Aboriginal tribes of Australia and Tribal Boundaries in Aboriginal Australia are the culmination of years of research, which are presented in his manuscripts. A list of manuscripts relevant to each language can be found on the South Australia Museum web site by searching Tindale's Catalogue of Australian Aboriginal Tribes (http://archives.samuseum.sa.gov.au/tribalmap/). ©Tony Tindale and Beryl George 1974. Courtesy of the South Australian Museum. You can find a language by language link between AustLang and this site under the Resource tab on the language information page.) - Triffitt, Geraldine. 2006. OZBIB : a linguistic bibliography of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands : supplement 1999-2006. Canberra: Mulini Press. URL: http://ozbib.aiatsis.gov.au

- Triffitt, Geraldine and Carrington, Lois. 1999. OZBIB : an Australian linguistic bibliography of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. URL: http://ozbib.aiatsis.gov.au

- Wafer, Jim and Lissarrague, Amanda. 2008. A handbook of Aboriginal languages of New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory. Nambucca Heads: Muurrbay ALCC.

- Walsh, Michael. 1981. Maps of Australia and Tasmania. In Wurm, S A, and Hattori, Shirô, eds, Language atlas of the Pacific area, 1. Canberra: Australian Academy of the Humanities. © Australian Academy of the Humanities. Information used with permission from the Australian Academy of the Humanities.

- Wurm, Stephen. 1972. Languages of Australia and Tasmania. The Hague: Mouton.

Call numbers are provided in a reference where a manuscript, audio or audio visual materials are held at AIATSIS, for example MS 1720, or JOHNSON_S01. If an item held in AILEC – Australian Indigenous Languages Electronic Collection – its item number is cited preceded by AILEC,for example: AILEC 0802.

Abbreviations

The following is a list of abbreviations used in AustLang. There are other abbreviations used in the headings.

|

ABS |

Australian Bureau of Statistics |

|

AIATSIS |

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies |

| AILEC | Australian Indigenous Languages Electronic Catalogue |

|

ALRRC |

NSW Aboriginal Languages Research and Resource Centre. 2007. The Aboriginal Languages of NSW (CD-ROM). © 2007 NSW Department of Aboriginal Affairs |

|

ASEDA |

Aboriginal Indigenous Languages Electronic Archive (formerly ASEDA, the Aboriginal Studies Electronic Data Archive; this category is now known as AILEC) |

|

Atlas |

Walsh, Michael. 1981. Maps of Australia and Tasmania. In Wurm, S A, and Hattori, Shirô, eds, Language atlas of the Pacific area, 1. Canberra: Academy of the Humanities. |

|

Ethnologue |

Gordon, Raymond G., Jr (ed.) 2005. Ethnologue: Languages of the World (15th edition) |

|

Horton |

Horton, David 1996, Aboriginal Australia. Canberra: AIATSIS |

|

Glottolog |

A comprehensive reference information for the world's languages, especially the lesser known languages. glottolog.org |

|

ILDB |

Thieberger, Nick, ILDB (Indigenous Language Database, Filemaker database) |

|

Kimberley (Handbook) |

McGregor, William 1988, Handbook of Kimberley languages. Series title: Pacific Linguistics Series C-105. Canberra: RSPAS, ANU |

|

MURA |

AIATSIS Library and Audio-visual archive catalogue |

|

NBA |

National Bibliographic Network |

|

NILS

NILR |

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. 2005. National Indigenous Languages Survey report 2005. Canberra: Department of Communication, Information Technology, and the Arts National Indigenous Languages Report 2019. |

|

OZBIB |

Linguistic Bibliography of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands |

|

SCAL |

Nash, David and Menning, Kathleen 1981, Sourcebook for Central Australian Languages. Alice Springs: Institute of Aboriginal Development |

|

Language Thesaurus |

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Pathways Language and Peoples Thesaurus (discontinued). |

|

Tindale |

Tindale, Norman. 1974. Aboriginal tribes of Australia: their terrain, environmental controls, distribution, limits, and proper names. Berkeley: University of California Press © Tony Tindale and Beryl George 1974. Courtesy of the South Australian Museum |

|

Top End Hanbook |

Baker, Brett. New Top End Handbook (FileMaker database). (ASEDA 0626). |

|

WA Handbook |

Thieberger, Nick. 1993. Handbook of Western Australian Aboriginal languages south of the Kimberley region. Series title: Pacific Linguistics Series C-124. Canberra: RSPAS, ANU |

|

VACL |

Victorian Aboriginal Corporation for Languages |

|

Wangka Maya PALC |

Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Languguage Centre |

Understanding a language variety record

A language information page has the AIATSIS code and AustLang reference name as the heading and provides basic information collected from a number of referenced sources. The information has not been assessed for its validity or truthfulness, and AIATSIS neither endorses nor refutes the information. Users are strongly encouraged to examine the referenced source materials.

The information is arranged under the following headings:

- Name

- Comment

- Location

- Catalogue

- Links

- Programs

- Speakers

- Documentation

Name

The names page contains the AustLang reference name for example C14: Alyawarr. This is followed by versions of this name used by various national and international agencies and language surveys, which in turn support the fuzzy search capacity of AustLang.

Thesaurus authority headings for languages and peoples are included for the benefit of collecting institutions. In general, they follow the elements of the reference name in a different order and separate them with the words ‘language’ and ‘people’, for example Alyawarr language C14 and Alyawarr people C14.

In some cases the people name is different from the language name, illustrated by the case of Australian people who speak the English language. For example: Yintyingka language Y236 is affiliated with Lamalama people Y236. Lamalama people are also affiliated with other Cape York languages, For example Umpitham language Y50 is affiliated with Lamalama people Y50.

IIn contrast for example S47: Walgalu is affiliated with several people groups which share a code: Ngambri people S47; Ngurmal people S47 and Walgalu people S47.

Comment

A Comment provides information about the language variety, including relationships with other varieties (where available). In citing information, language names are written as they are in the source material. When this is different from the AustLang reference name, the AIATSIS code follows to ensure the reader can track the language identity. Links via the alpha-numeric codes lead to related language varieties. Comments about a language variety may differ between sources.

The Status field distinguishes different levels or degrees of certainty about names. There are four status levels:

|

Confirmed |

Names which are accepted to refer to a language/dialect by linguists. |

|

Unconfirmed |

Names which are unlikely to be a language/dialect name. This may be because linguists identified them to be a place, person or group name or as an alternative name/variant of another language identified elsewhere in the database, or there is hardly any evidence to prove them to be a language/dialect name. |

|

Potential with data (Potential data) |

Names whose identity is uncertain because of limited information available. Language data (word list, phrases, etc.) is available according to the AIATSIS catalogue, MURA. |

|

Potential with no data (Potential no data) |

Names whose identity is uncertain because of limited information available. No language data (word list, phrases, etc.) is available according to the AIATSIS catalogue, MURA. |

Location

When available, written descriptions of the location of a language are provided. The location provided on the accompanying maps are based on these descriptions, as well as cited maps. Note that in identifying the location, Norman Tindale's Aboriginal tribes of Australia and Tribal Boundaries in Aboriginal Australia (map) was used (and quoted/cited) only when no other information was available, or the information found in Tindale's work overlaps with other available information.

Links

Where available, links include:

- MURA, the AIATSIS collection catalogue for material about the specific language or affiliated people in the AIATSIS Collection

- Oates (for the 1973 supplement ...) 1975

- Tindale 1974, South Australian Museum

- Ethnologue Languages of the World (15th edition) 2005

- WA Handbook (Thieberger 1993)

- Kimberley Handbook (McGregor 1998)

- SCAL (Nash and Menning 1981)

- OLAC Open languages Archive Community

- SIL Summer Institute of Linguistics

- other community-based online resources

Programs

Includes links or information about Activities, People and Indigenous Organisations where known.

Speakers

Information on speaker numbers as found in different surveys or census.

|

Oates 1973 |

Oates, Lynette. 1975. The 1973 supplement to a revised linguistic survey of Australia |

|

Senate 1984 |

Senate Standing Committee on Education and the Arts. 1984. A National Language Policy |

|

Schmidt 1990 |

Schmidt, Annette. 1990. The loss of Australia's Aboriginal language heritage |

|

Census 1996 |

Australian Bureau of Statistics 1996 Census |

|

Census 2001 |

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2001 Census |

|

NILS 2004 |

National Indigenous Languages Survey 2004 |

|

2005 estimate |

Estimated speaker numbers as reported in National Indigenous Languages Survey Report 2005 |

|

Census |

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006, 2011, 2016 |

Please note: Regarding the Census data, ABS's Australian Standard Classification of Languages 1997 (ASCL) separately identifies 50 Australian Indigenous languages. ABS released the second edition of ASCL in 2005 and this separately identifies 155 Indigenous languages. In the Census result, the number of speakers of a not-separately-identified-language is included in the number given for a ‘not elsewhere classified' category, such as ‘Cape York Peninsula Languages' or ‘Northern Desert Fringe Area Languages'. For example, Wagiman is not separately identified in ASCL but listed under the ‘Arnhem Land and Daly River Region Languages' category. The speaker number of Wagiman is then included in the total number of speakers of all languages listed under this category. If a language name is not listed in ASCL at all, the number of speakers for that language is included in the number of speakers given for a ‘not further defined' (nfd) category. Consequently, it is impossible to tell from the published Census data how many speakers actually exist for languages which are not separately identified in ASCL.

The Australian Standard Classification of Languages (ASCL) does not list all (or even most) of the approximately 6,000 languages spoken worldwide. In order to be separately identified in ASCL, a non-Indigenous language must have 100 or more speakers in Australia. For Australian Indigenous languages the minimum threshold is three known speakers.

The 2011 and 2016 ABS data includes 217 language varieties under the headings:

Arnhem Land and Daly River Region languages (including a category nec: not elsewhere categorised); Yolngu Matha (including Other Yolngu nec); Cape York Peninsula Languages (including CYP Languages nec); Torres Strait Island Languages; Northern Desert Fringe Area Languages (including Northern Desert Fringe Area Languages nec); Arandic (including Arrernte and Arandic nec); Western Desert Languages (including Western Desert languages nec); Kimberley Area languages (including Kimerley Area languages nec); Other Australian Indigenous Languages (including Other Australian Indigenous Languages nec); Aboriginal English.

Documentation

Documentation scores convey information about four formats: word lists/dictionaries, texts/stories, grammars, and audio-visual.

Documentation scores were calculated on the basis of materials held In the AIATSIS collection (see MURA) including AILEC, and in OZBIB.

The 'unclear status' of a language means that an item is described as on a number of languages in MURA, but it is not clear whether the item contains data on all of these languages. ‘Unclear status' also applies where an item is described as on a certain language but the explanatory notes for the item suggest that the item actually does not contain information about this language.

The scoring is based on the scoring system employed by the National Indigenous Languages Survey conducted by AIATSIS and FATSIL in 2004. Scoring for dictionary/word list, texts/stories, and grammar was conducted by Kazuko Obata from February to June 2006, while scoring for audio-visual items was undertaken by Sally McNicol as part of the Survey in late 2004. The latter was partially updated by Kazuko Obata in 2007.

The following table shows the scoring system employed by the Survey. The scores do not correspond to the number of items.

Word list / Dictionary; Texts / Stories

Large (more than 200 pages) 4

Medium (100 – 200 pages) 3

Small (20 – 100 pages) 2

Less than 20 pages 1

None 0

Word list / Dictionary

Items subject to scoring included published items, manuscripts and field notes where items clearly included a word list/dictionary of a particular language with some indication of the extent of data (by page numbers or the number of words).

Items which list only place names, kinship terms or flora terms are excluded.

Items by Daisy Bates (Daisy Bates, 1859-1951, collected data on languages from the north-western Australia. Most of her items are manuscripts) are included in scoring only when the item clearly contains data on a particular language. Otherwise, they are not subject to scoring and are included in the manuscript/field notes.

Where a word list/dictionary have more than one part, eg. Indigenous-English, English-Indigenous, alphabetical and/or semantic fields, scores were worked out according to the number of pages for the Indigenous-English part or alphabetical part only.

Texts / stories

Items subject to scoring included published texts, books, and booklets. Readers for literacy programs are included but not alphabet/orthography books or booklets which list some words or expressions only.

Tape transcriptions and field notes are included when MURA clearly indicates what kind of data and how much data they contain (often these are transcriptions or field notes which have undergone some processing, e.g. transcriptions with translations, or typed rather than photocopied field notes).

Elicited sentences were also subject to scoring.

Daisy Bates' items are subject to scoring but note that many of her items contain very limited data, comprising a few sentences or words.

Songs are also included, although it is preferable to categorise them separately.

Grammar

Large grammar (more than 200 pages) 4

Small grammar (100 – 200 pages) 3

Sketch grammar 2

A few articles 1

None 0

- Some of items that were subject to scoring cover only limited topic(s) of grammar, e.g. morphology.

- If an item also contains a word list and/or text, only the number of pages for grammatical description is considered for scoring in this category.

Audio

More than 10 hours of audio 3

Between 1 and 10 hours of audio 2

Less than an hour of audio 1

None 0

- Items subject to scoring were materials held at the AIATSIS audio-visual archive. Scoring was done on the basis of documentation (audition sheets) on each material.

Manuscripts/field notes

- If a manuscripts/field note was subject to scoring in one of the other categories (dictionary/word list, texts/stories or grammar), it was not included under manuscripts/field notes.

- Where a manuscript/field note contains only vocabulary, songs, or sentences, it is indicated so as much as possible.

Documentation scores are a guide only. Users are strongly encouraged to consult MURA, OZBIB, and AILEC. Some dictionaries contain examples and this increases the number of pages. On the other hand, some texts contain only original texts and their translation while others contain word by word translation or segmented texts, increasing the number of pages. Comparison of scores across different languages may not be helpful since scores can only be compared by the number of pages not by the number of dictionary entries or the number of lines in Indigenous languages. It is ideal to have a scoring system with the number of entries or lines but implementation of such a scoring system requires substantial resources. currently unavailable. It is also difficult to compare the quality of different items.

Classification

Classifications of Indigenous Australian languages from Ethnologue (2005); Dixon (2002); Wurm (1994 and 1972); Walsh (1981); Oates (1975), O’Grady, Voegelin & Voegelin (1966) are listed. Two major classifications used by linguists are Pama-Nyungan and non-Pama-Nyungan. These represent two language families, Pama-Nyungan covers most of the continent and non-Pama-Nyungan languages are restricted to the top end of the NT and WA. Languages within each family share many grammatical features and cognates.